7

Canonical Perturbation Theory

Having treated the motion of the moon about the earth, and having obtained an elliptical orbit, [Newton] considered the effect of the sun on the moon’s orbit by taking into account the variations of the latter. However, the calculations caused him great difficulties … Indeed, the problems he encountered were such that [Newton] was prompted to remark to the astronomer John Machin that “… his head never ached but with his studies on the moon.”

June Barrow-Green, Poincaré and the Three Body Problem [7], p. 15

Closed-form solutions of dynamical systems can be found only rarely. However, some systems differ from a solvable system by the addition of a small effect. The goal of perturbation theory is to relate aspects of the motion of the given system to those of the nearby solvable system. We can try to find a way to transform the exact solution of this approximate problem into an approximate solution to the original problem. We can also use perturbation theory to try to predict qualitative features of the solutions by describing the characteristic ways in which solutions of the solvable system are distorted by the additional effects. For instance, we might want to predict where the largest resonance regions are located or the locations and sizes of the largest chaotic zones. Being able to predict such features can give insight into the behavior of the particular system of interest.

Suppose, for example, we have a system characterized by a Hamiltonian that breaks up into two parts as follows:

where H0 is solvable and ϵ is a small parameter. The difference between our system and a solvable system is then a small additive complication.

There are a number of strategies for doing this. One strategy is to seek a canonical transformation that eliminates from the Hamiltonian the terms of order ϵ that impede solution—this typically introduces new terms of order ϵ2. Then one seeks another canonical transformation that eliminates the terms of order ϵ2 impeding solution, leaving terms of order ϵ3. We can imagine repeating this process until the part that impedes solution is of such high order in ϵ that it can be neglected. Having reduced the problem to a solvable problem, we can reverse the sequence of transformations to find an approximate solution of the original problem. Does this process converge? How do we know we can ever neglect the remaining terms? Let’s follow this path and see where it goes.

7.1 Perturbation Theory with Lie Series

Given a system, we look for a decomposition of the Hamiltonian in the form

where H0 is solvable. We assume that the Hamiltonian has no explicit time dependence; this can be ensured by going to the extended phase space if necessary. We also assume that a canonical transformation has been made so that H0 depends solely on the momenta:

We carry out a Lie transformation and find the conditions that the Lie generator W must satisfy to eliminate the order ϵ terms from the Hamiltonian.

The Lie transform and associated Lie series specify a canonical transformation:

where Q = I1 and P = I2 are the coordinate and momentum selectors and I is the identity function. Recall the definitions

with LWF = {F, W }.

Applying the Lie transformation to H gives us

The first-order term in ϵ is zero if W satisfies the condition

which is a linear partial differential equation for W. The transformed Hamiltonian is

where we have used condition (7.7) to simplify the ϵ2 contribution.

This basic step of perturbation theory has eliminated terms of a certain order (order ϵ) from the Hamiltonian, but in doing so has generated new terms of higher order (here ϵ2 and higher).

At this point we can find an approximate solution by truncating Hamiltonian (7.8) to H0, which is solvable. The approximate solution for given initial conditions s0 = (t0, q0, p0) is obtained by finding the corresponding

using the identity (6.111). Notice that the time evolution of H0 is expressed in terms of the evolution operator E rather than the Lie-transform operator E′, because the time must also be advanced. The power-series expansion for

Assuming everything goes okay, we can imagine repeating this process to eliminate the order ϵ2 terms and so on, bringing the transformed Hamiltonian as close as we like to H0. Unfortunately, there are complications. We can understand some of these complications and how to deal with them by considering some specific applications.

7.2 Pendulum as a Perturbed Rotor

The pendulum is a simple one-degree-of-freedom system, for which the solutions are known. If we consider the pendulum as a free rotor with the added complication of gravity, then we can carry out a perturbation step as just described to see how well it approximates the known motion of the pendulum.

The motion of a pendulum is described by the Hamiltonian

with coordinate θ and conjugate angular momentum p, where α = ml2 and β = mgl. The parameter ϵ allows us to scale the perturbation; it is 1 for the actual pendulum. We divide the Hamiltonian into the free-rotor Hamiltonian and the perturbation from gravity:

where

The Lie generator W satisfies condition (7.7):

or

So

where the arbitrary integration constant is ignored.

The transformed Hamiltonian is H′ = H0 + o(ϵ2). If we can ignore the ϵ2 contributions, then the transformed Hamiltonian is simply

with solutions

To connect these solutions to the solutions of the original problem, we use the Lie series

Similarly,

Note that if the Lie series is truncated it is not exactly a canonical transformation; only the infinite series is canonical.

The initial values

and

Note that if we truncate the coordinate transformations after the first-order terms in ϵ (or any finite order), then the inverse transformation is not exactly the inverse of the transformation.

The approximate solution for given initial conditions (t0, θ0, p0) is obtained by finding the corresponding

We define the two parts of the pendulum Hamiltonian:

(define ((H0 alpha) state)

(let ((p (momentum state)))

(/ (square p) (* 2 alpha))))

(define ((H1 beta) state)

(let ((theta (coordinate state)))

(* -1 beta (cos theta))))

The Hamiltonian for the pendulum can be expressed as a series expansion in the parameter ϵ by

(define (H-pendulum-series alpha beta epsilon)

(series (H0 alpha) (* epsilon (H1 beta))))

where the series procedure is a constructor for a series whose first terms are given and all further terms are zero. The Lie generator that eliminates the order ϵ terms is

(define ((W alpha beta) state)

(let ((theta (coordinate state))

(p (momentum state)))

(/ (* -1 alpha beta (sin theta)) p)))

We check that W satisfies condition (7.7):

((+ ((Lie-derivative (W ’alpha ’beta)) (H0 ’alpha))

(H1 ’beta))

(up ’t ’theta ’p))

0

and that it has the desired effect on the Hamiltonian:

(show-expression

(series:sum

(((exp (* ’epsilon (Lie-derivative (W ’alpha ’beta))))

(H-pendulum-series ’alpha ’beta ’epsilon))

(up ’t ’theta ’p))

2))

Indeed, the order ϵ term has been removed and an order ϵ2 term has been introduced.

Ignoring the ϵ2 terms in the new Hamiltonian, the solution is

(define (((solution0 alpha beta) t) state0)

(let ((t0 (time state0))

(theta0 (coordinate state0))

(p0 (momentum state0)))

(up t

(+ theta0 (/ (* (- t t0) p0) alpha))

p0)))

The transformation from primed to unprimed phase-space coordinates is, including terms up to order,

(define ((C alpha beta epsilon order) state)

(series:sum

(((Lie-transform (W alpha beta) epsilon)

identity)

state)

order))

To second order in ϵ the transformation generated by W is

(show-expression

((C ’alpha ’beta ’epsilon 2) (up ’t ’theta ’p)))

The inverse transformation is

(define (C-inv alpha beta epsilon order)

(C alpha beta (- epsilon) order))

With these components, the perturbative solution (equation 7.9) is

(define (((solution epsilon order) alpha beta) delta-t)

(compose (C alpha beta epsilon order)

((solution0 alpha beta) delta-t)

(C-inv alpha beta epsilon order)))

The resulting procedure maps an initial state to the solution state advanced by delta-t.

We can examine the behavior of the perturbative solution and compare it to the true behavior of the pendulum. There are several considerations. We have truncated the Lie series for the phase-space transformation. Does the missing part matter? If the missing part does not matter, how well does this perturbation step work?

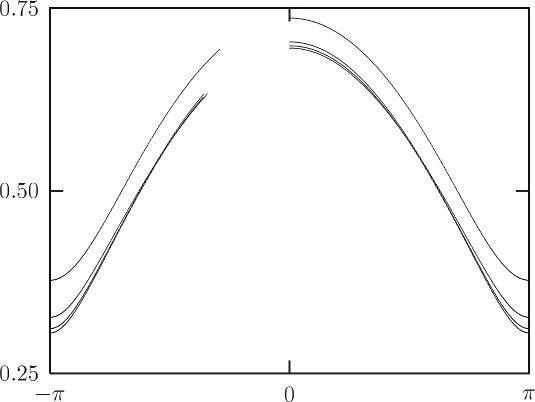

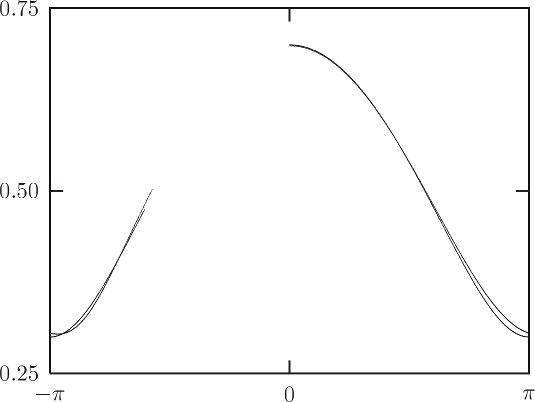

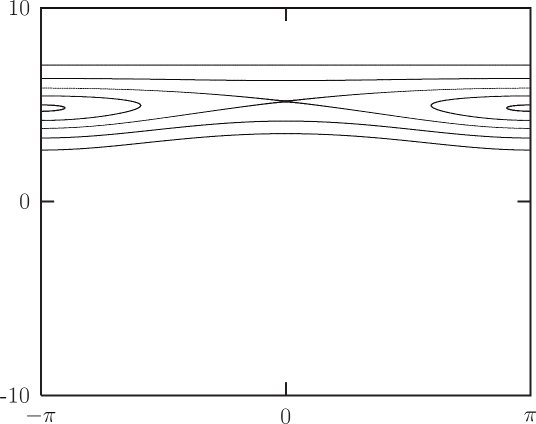

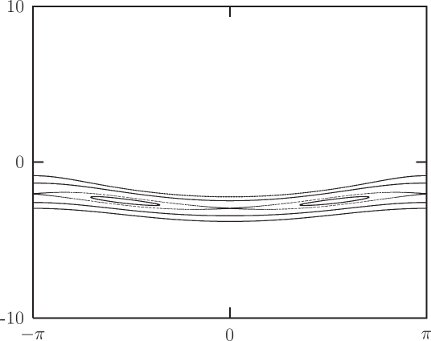

Figure 7.1 shows that as we increase the number of terms in the Lie series for the phase-space coordinate transformation the result appears to converge. The lone trajectory includes only terms of first order. The others, including terms of second, third, and fourth order, are closely clustered. On the left edge of the graph (at θ = −π), the order of the solution increases from the top to the bottom of the graph. In the middle (at θ = 0), the fourth-order curve is between the second-order curve and the third-order curve. In addition to the error in phase-space path, there is also an error in the period—the higher-order orbits have longer periods than the first-order orbit. The parameters are α = 1.0 and β = 0.1. We have set ϵ = 1. Each trajectory was started at θ = 0 with p = 0.7. Notice that the initial point on the solution varies between trajectories. This is because the transformation is not perfectly inverted by the truncated Lie series.

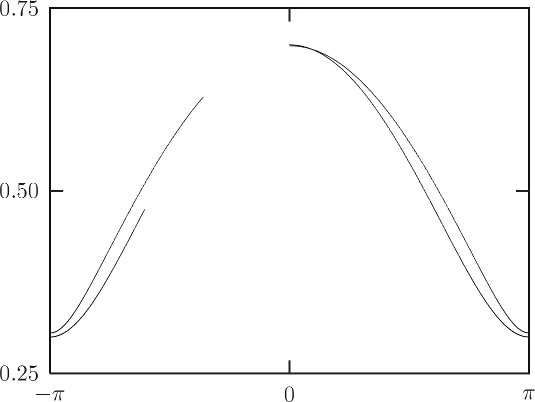

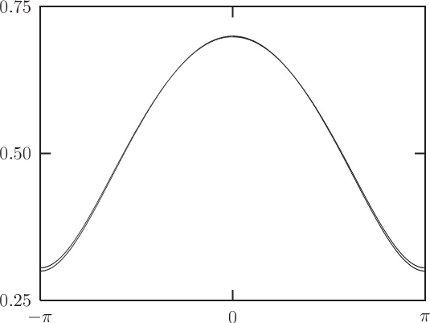

Figure 7.2 compares the perturbative solution (with terms up to fourth order) with the actual trajectory of the pendulum. The initial points coincide, to the precision of the graph, because the terms to fourth order are sufficient. The trajectories deviate both in the phase plane and in the period, but they are still quite close.

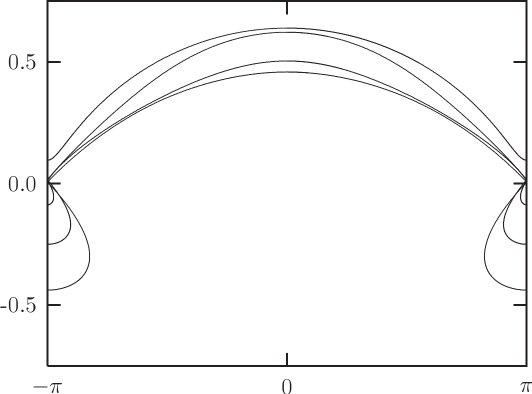

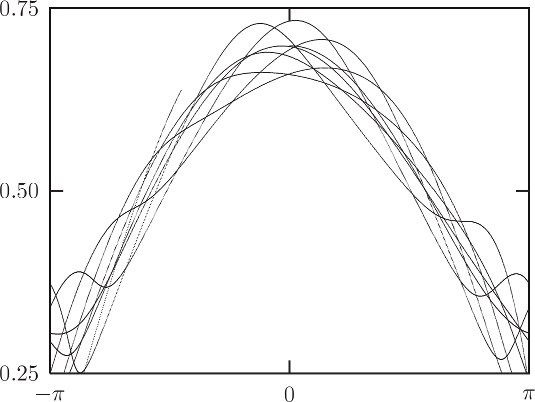

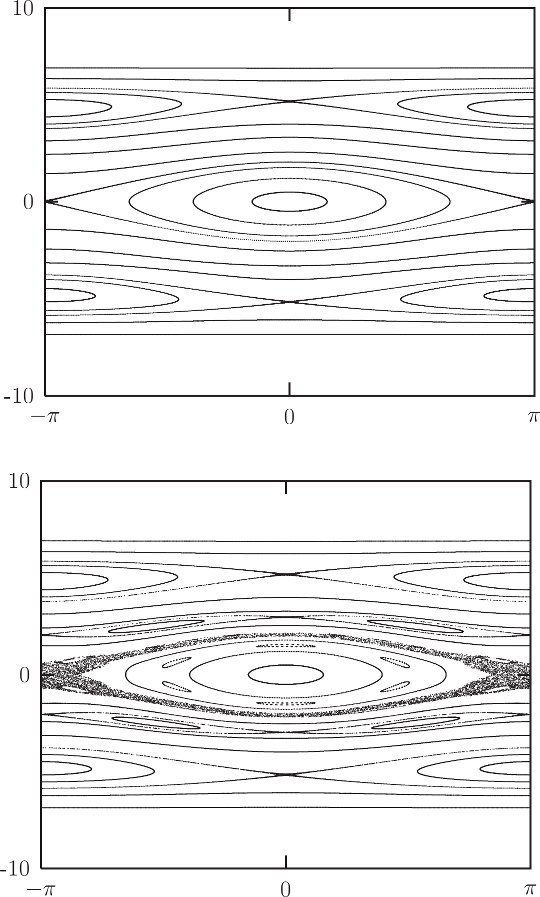

The trajectories of figures 7.1 and 7.2 are all for the same initial state. As we vary the initial state we find that for trajectories in the circulation region, far from the separatrix, the perturbative solution does quite well. However, if we get close to the separatrix or if we enter the oscillation region, the perturbative solution is nothing like the real solution, and it does not even seem to converge. Figure 7.3 shows what happens when we try to use the perturbative solution inside the oscillation region. Each trajectory was started at θ = 0 with p = 0.55. The parameters are α = 1.0 and β = 0.1, as before.

This failure of the perturbation solution should not be surprising. We assumed that the real motion was a distorted version of the motion of the free rotor. But in the oscillation region the assumption is not true—the pendulum is not rotating at all. The perturbative solutions can be valid (if they work at all!) only in a region where the topology of the real orbits is the same as the topology of the perturbative solutions.

We can make a crude estimate of the range of validity of the perturbative solution by looking at the first correction term in the phase-space transformation (7.18). The correction in θ is proportional to ϵαβ/(p′)2. This is not a small perturbation if

This sets the scale for the validity of the perturbative solution.

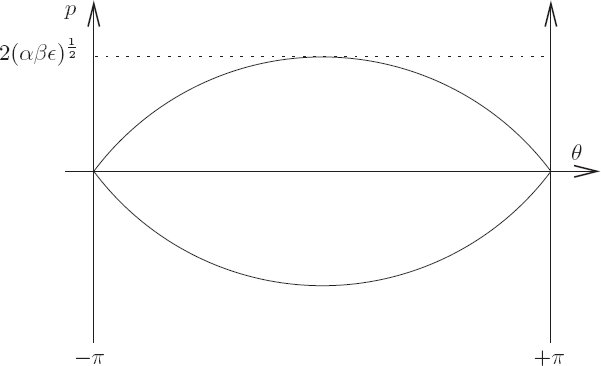

We can compare this scale to the size of the oscillation region (see figure 7.4). We can obtain the width of the region of oscillation of the pendulum1 by considering the separatrix. The value of the Hamiltonian on the separatrix is the same as the value at the unstable equilibrium: H(t, θ = π, p = 0) = βϵ. The separatrix has maximum momentum psep at θ = 0:

Solving for psep, the half-width of the region of oscillation, we find

Comparing equations (7.22) and (7.24), we see that the requirement that the terms in the perturbation solution be small excludes a region of the phase space with the same scale as the region of oscillation of the pendulum.

What the perturbation theory is doing is deforming the phase-space coordinate system so that the problem looks like the free-rotor problem. This deformation is sensible only in the circulating case. So, it is not surprising that the perturbation theory fails in the oscillation region. What may be surprising is how well the perturbation theory works just outside the oscillation region. The range of p in which the perturbation theory is not valid scales in the same way as the width of the oscillation region. This need not have been the case—the perturbation theory could have failed over a wider range.

Exercise 7.1: Symplectic residual

For the transformation (C alpha beta epsilon order), compute the residuals in the symplectic test for various orders of truncation of the Lie series.

7.2.1 Higher Order

We can improve the perturbative solution by carrying out additional perturbation steps. The overall plan is the same as before. We perform a Lie transformation with a new generator that eliminates the desired terms from the Hamiltonian.

After the first step the Hamiltonian is, to second order in ϵ,

Performing a Lie transformation with generator W′ yields the Hamiltonian

So the condition on W′ that the second-order terms are eliminated is

This is

A generator that satisfies this condition is

There are two contributions to this generator, one proportional to θ′ and the other involving a trigonometric function of θ′.

The phase-space coordinate transformation resulting from this Lie transform is found as before. For given initial conditions, we first carry out the inverse transformation corresponding to W, then that for W′, solve for the evolution of the system using H0, then transform back using W′ and then W. For initial state s0 = (t0, θ0, p0) and advanced state s = (t, θ, p), the approximate solution is

The solution obtained in this way is compared to the actual evolution of the pendulum in figure 7.5. Terms in all Lie series up to ϵ4 are included. The perturbative solution, including this second perturbative step, is much closer to the actual solution in the initial segment than the first-order perturbative solution (figure 7.2). The time interval spanned is 10. Over longer times the second-order perturbative solution diverges dramatically from the actual solution, as shown in figure 7.6. These solutions begin at θ = 0 with p = 0.7. The parameters are α = 1.0 and β = 0.1. The time interval spanned is 100.

A problem with the perturbative solution is that there are terms in W′ and in the corresponding phase-space coordinate transformation that are proportional to θ′, and θ′ grows linearly with time. So the solution can be valid only for small times; the interval of validity depends on the frequency of the particular trajectory under investigation and the size of the coefficients multiplying the various terms. Such terms in a perturbative representation of the solution that are proportional to time are called secular terms. They limit the validity of the perturbation theory to small times.

7.2.2 Eliminating Secular Terms

A solution to the problem of secular terms was developed by Lindstedt and Poincaré. The goal of each perturbation step is to eliminate terms in the Hamiltonian that prevent solution. However, the term in H′ that led to the secular term in the generator W′ does not actually impede solution. So a better procedure is to leave that term in the Hamiltonian and find the generator W″ that eliminates only the term that is periodic in θ′. So W″ must satisfy

The generator is

After we perform a Lie transformation with this generator, the new Hamiltonian is

Including terms up to the ϵ2 term, the solution is

We construct the solution for a given initial condition as before by composing the transformations, the solution of the modified Hamiltonian, and the inverse transformations. The approximate solution is

The resulting phase-space evolution is shown in figure 7.7. Now the perturbative solution is a closed curve in the phase plane and is in pretty good agreement with the actual solution.

By modifying the solvable part of the Hamiltonian we are modifying the frequency of the solution. The secular terms appeared because we were trying to approximate a solution with one frequency as a Fourier series with the wrong frequency. As an analogy, consider

The periodic terms are multiplied by terms that are polynomials in the time. These polynomials are the initial segment of the power series for periodic functions. The infinite series are convergent, but if the series are truncated the error is large at large times.

Continuing the perturbative solution to higher orders is now a straightforward repetition of the steps carried out so far. At each step in the perturbation solution there will be new contributions to the solvable part of the Hamiltonian that absorb potential secular terms. The contribution is just the angle-independent part of the Hamiltonian after the Hamiltonian is written as a Fourier series. The constant part of the Fourier series is the same as the average of the Hamiltonian over the angle. So at each step in the perturbation theory, the average of the perturbation is included with the solvable part of the Hamiltonian and the periodic part is eliminated by a Lie transformation.

7.3 Many Degrees of Freedom

Other problems are encountered in applying perturbation theory to systems with more than a single degree of freedom. Consider an n degrees-of-freedom Hamiltonian of the form

where H0 depends only on the momenta and therefore is solvable. We assume that the Hamiltonian has no explicit time dependence. We further assume that the coordinates are all angles and that H1 is a multiply periodic function of the coordinates.

Carrying out a Lie transformation with generator W produces the Hamiltonian

as before. The condition that the order ϵ terms are eliminated is

a linear partial differential equation. By assumption, the Hamiltonian H0 depends only on the momenta. We define

where θ = (θ0, …, θn−1), and p = [p0, …, pn−1]. So ω0(p) is the up tuple of frequencies of the unperturbed system. The condition on W is

As H1 is a multiply periodic function of the coordinates, we can write it as a Poisson series:2

where k = [k0, …, kn−1] ranges over all n-tuples of integers. Similarly, we assume W can be written as a Poisson series:

Substituting these into the condition that order ϵ terms are eliminated, we find

The cosines are orthogonal so the coefficients of corresponding cosine terms must be equal:

and that the required Lie generator is

There are a couple of problems. First, if A0,…,0 is nonzero then the expression for B0,…,0 involves a division by zero. So the expression for B0,…,0 is not correct. The problem is that the corresponding term in H1 does not involve θ. So the integration for B0,…,0 should introduce linear terms in θ. But this is the same situation that led to the secular terms in the perturbation approximation to the pendulum. Having learned our lesson there, we avoid the secular terms by adjoining this term to the solvable Hamiltonian and excluding k = [0, …, 0] from the sum for W. We have

and

Another problem is that there are many opportunities for small denominators that would make the perturbation large and therefore not a perturbation. As we saw in the perturbation approximation for the pendulum in terms of the rotor, we must exclude certain regions from the domain of applicability of the perturbation approximation. These excluded regions are associated with commensurabilities among the frequencies ω0(p). Consider the phase-space transformation of the coordinates

We must exclude from the domain of applicability all regions for which the coefficients are large. If the second term in the coefficient of sin dominates, the excluded regions satisfy

Considering the fact that for any tuple of frequencies ω0(p′) we can find a tuple of integers k such that k·ω(p′) is arbitrarily small, this problem of small divisors looks very serious.

However, the problem, though serious, is not as bad as it may appear, for a couple of reasons. First, it may be that Ak ≠ 0 only for certain k. In this case, only the regions for these terms are excluded from the domain of applicability. Second, for analytic functions the magnitude of Ak decreases strongly with the size of k (see [4]):

for some positive β and C, and where |k|+ = |k0| + |k1| + ⋯. At any stage of a perturbation approximation we can limit consideration to just those terms that are larger than a specified magnitude. The size of the excluded region corresponding to a term is of order square root of |Ak(p′)| and the inequality (7.51) shows that |Ak(p′)| decreases exponentially with the order of the term.

7.3.1 Driven Pendulum as a Perturbed Rotor

More concretely, consider the periodically driven pendulum. We will develop approximate solutions for the driven pendulum as a perturbed rotor.

We use the Hamiltonian

For a real driven pendulum ϵ = 1; here it is used to help organize the computation. We will see that it need not be small and can be set to 1 at the end. We can remove the explicit time dependence by going to the extended phase space. The Hamiltonian is

with the constants α = ml2, β = mlg, and

With the intent to approximate the driven pendulum as a perturbed rotor, we choose

The perturbation H1 is particularly simple: it has only three terms, and the coefficients are constants. Because H1 has only three terms in its Poisson series, only three regions will be excluded from the domain of applicability in the first perturbation step.

The Lie series generator that eliminates the terms in H1 to first order in ϵ, satisfying

is

where ωr(p) = ∂2,0H0(τ; θ, t; p, pt) = p/α is the unperturbed rotor frequency.

The resulting approximate solution has three regions in which there are small denominators, and so three regions that are excluded from applicability of the perturbative solution. Regions of phase space for which ωr(p) is near 0, ω, and −ω are excluded. Away from these regions the perturbative solution works well, just as in the rotor approximation for the pendulum. Unfortunately, some of the more interesting regions of the phase space of the driven pendulum are excluded: the region in which we find the remnant of the undriven pendulum is excluded, as are the two resonance regions in which the rotation of the pendulum is synchronous with the drive. We need to develop methods for approximating these regions.

7.4 Nonlinear Resonance

We can develop an approximation for an isolated resonance region as follows. We again consider Hamiltonians of the form

where H0(t, q, p) = Ĥ0(p) depends only on the momenta and so is solvable. We assume that the Hamiltonian has no explicit time dependence. We further assume that the coordinates are all angles, and that H1 is a multiply periodic function of the coordinates that can be written

Suppose we are interested in a region of phase space for which n · ω0(p) is near zero, where n is a tuple of integers, one for each degree of freedom. If we develop the perturbation theory as before with the generator W that eliminates all terms of order ϵ, then the transformed Hamiltonian is H0, which is analytically solvable, but there would be terms with n · ω0(p) in the denominator. The resulting solution is not applicable near this resonance.

Just as the problem of secular terms was solved by grouping more terms with the solvable part of the Hamiltonian, we can develop approximations that are valid in the resonance region by eliminating fewer terms and grouping more terms in the solvable part.

To develop a perturbative approximation in the resonance region for which n · ω0(p) is near zero, we take the generator W to be

excluding terms in W that lead to small denominators in this region. The transformed Hamiltonian is

where the additional terms are higher-order in ϵ. Because the term k = n is excluded from the sum in the generating function, that term is left after the transformation.

The transformed Hamiltonian depends only on a single combination of angles, so a change of variables can be made so that the new transformed Hamiltonian is cyclic in all but one coordinate, which is this combination of angles. This transformed Hamiltonian is solvable (reducible to quadratures).

For example, suppose there are two degrees of freedom θ = (θ1, θ2) and we are interested in a region of phase space in which n · ω0 is near zero, with n = [n1, n2]. The combination of angles n · θ is slowly varying in the resonance region. The transformed Hamiltonian (7.60) is of the form

We can transform variables to σ = n1θ1 + n2θ2, with second coordinate, say, θ′ = θ2.3 Using the F2-type generating function

we find that the transformation is

In these variables the transformed resonance Hamiltonian

This Hamiltonian is cyclic in θ′, so Θ′ is constant. With this constant momentum, the Hamiltonian for the conjugate pair (σ, Σ) has one degree of freedom. The solutions are level curves of the Hamiltonian. These solutions, reexpressed in terms of the original phase-space coordinates, give the evolution of

If the resonance regions are sufficiently separated, then a global solution can be constructed by splicing together such solutions for each resonance region.

7.4.1 Pendulum Approximation

The resonance Hamiltonian (7.64) has a single degree of freedom and is therefore solvable (reducible to quadratures). We can develop an approximate analytic solution in the vicinity of the resonance by making use of the fact that the solution is valid there. The resonance Hamiltonian can be approximated by a generalized pendulum Hamiltonian.

Let

and

then the resonance Hamiltonian is

Define the resonance center Σn by the requirement that the resonance frequency be zero there:

Now expand both parts of the resonance Hamiltonian about the resonance center:

and

The first term in the expansion of

which is the Hamiltonian for a pendulum with a shifted center in momentum. This is analytically solvable. The constants are:

Driven pendulum resonances

Consider the behavior of the periodically driven pendulum in the vicinity of the resonance ωr(p) = ω.

The Hamiltonian (7.54) for the driven pendulum has three resonance terms in H1. The full generator (7.56) has three terms that are designed to eliminate the corresponding resonance terms in the Hamiltonian. The resulting approximate solution has small denominators close to each of the three resonances, ωr(p) = 0, ωr(p) = ω, and ωr(p) = −ω.

To develop a resonance approximation near ωr(p) = ω, we do not include the corresponding term in the generator, so that the corresponding term is left in the Hamiltonian. It is helpful to give names to the various terms in the full generator (7.56):

The full generator is W0 + W− + W+.

To investigate the motion in the phase space near the resonance ωr(p) = ω (the “+” resonance), we use the generator that excludes the corresponding term

With this generator the transformed Hamiltonian is

After we exclude the higher-order terms, this Hamiltonian has only a single combination of coordinates, and so can be transformed into a Hamiltonian that is cyclic in all but one degree of freedom. Define the transformation through the mixed-variable generating function

giving the transformation

Expressed in these new coordinates, the resonance Hamiltonian is

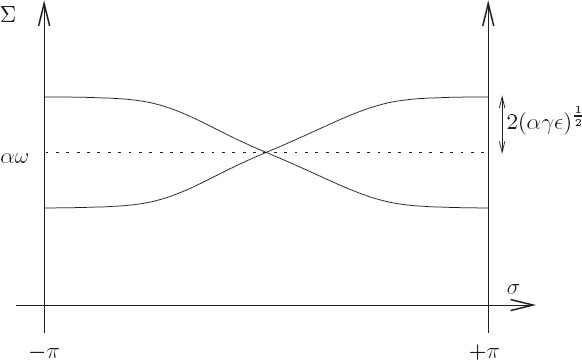

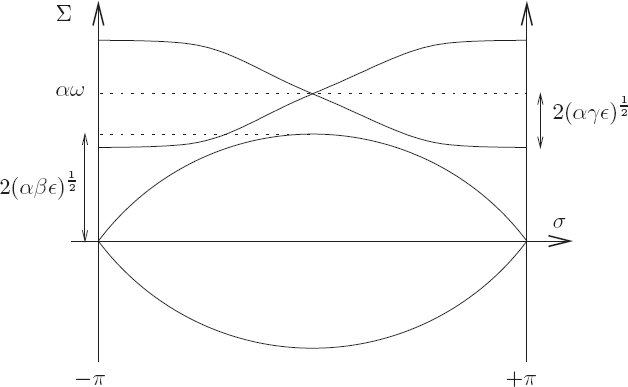

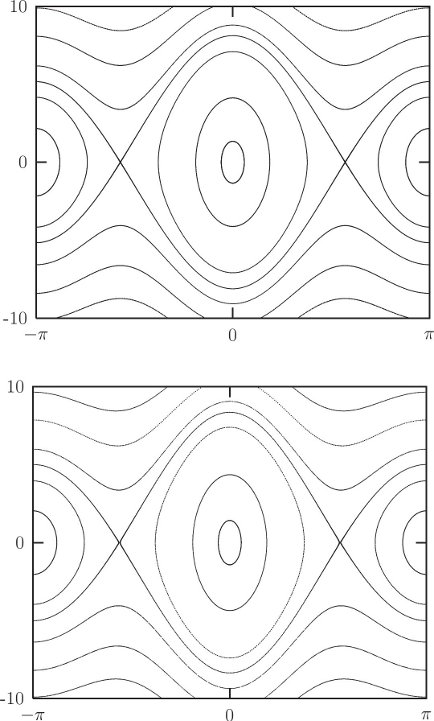

This Hamiltonian is cyclic in t′, so the solutions are level curves of H+′ in (σ, Σ). Actually, more can be said here because H+′ is already of the form of a pendulum shifted in the Σ direction by αω and shifted by π in phase. The shift by π comes about because the sign of the cosine term is positive, rather than negative as in the usual pendulum. A sketch of the level curves is given in figure 7.8.

Exercise 7.2: Resonance width

Verify that the half-width of the resonance region is

Exercise 7.3: With the computer

Verify, with the computer, that with the generator W+ the transformed Hamiltonian is given by equation (7.76).

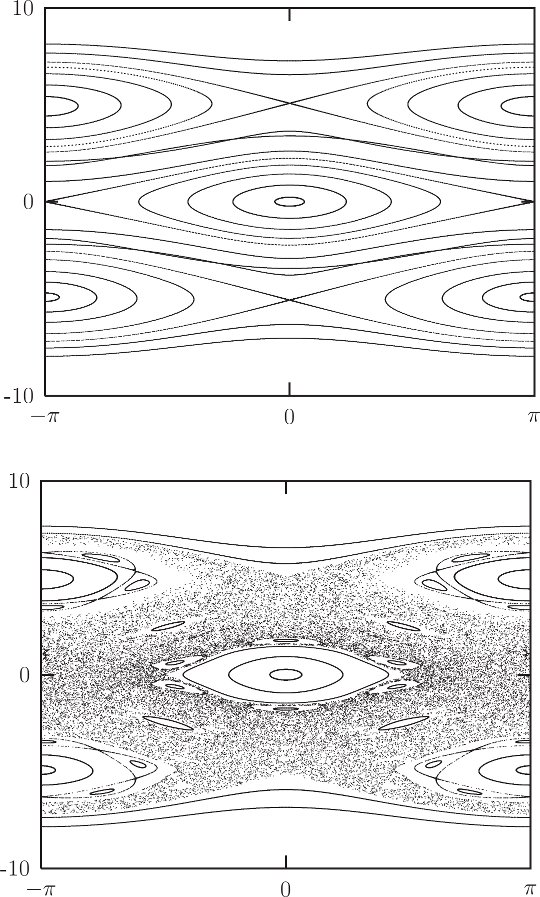

An approximate solution of the driven pendulum near the ωr(p) = ω resonance is

To find out to what extent the approximate solution models the actual driven pendulum, we make a surface of section using this approximate solution and compare it to a surface of section for the actual driven pendulum. The surface of section for the approximate solution in the resonance region is shown in figure 7.9. A surface of section for the actual driven pendulum is shown in the lower part of figure 7.10. The correspondence is surprisingly good. Note how the resonance island is not symmetrical about a line of constant momentum. The resonance Hamiltonian is symmetrical about Σ = αω, and by itself would give a symmetric resonance island (see figure 7.8). The necessary distortion is introduced by the W+ transformation that eliminates the other resonances. Indeed, in the full section the distortion appears to be generated by the nearby ωr(p) = 0 resonance “pushing away” nearby features so that it has room to fit. However, some features of the actual section are not represented in figure 7.9: for instance, the small chaotic zone near the actual separatrix.

The distortion introduced by the transformation generated by W+ is small because the terms that it introduces are proportional to the inverse of a combination of frequencies.4 Since this combination is not small, dividing by it makes the correction small. Thus the “order parameter” ϵ need not be small to make the correction terms small, and from now on we can set ϵ = 1.

The perturbation solution near the ωr(p) = 0 resonance merges smoothly with the perturbation solutions for the ωr(p) = ω and ωr(p) = −ω resonances. We can make a composite perturbative solution by using the appropriate resonance solution for each region of phase space. A surface of section for the composite pertur-bative solution is shown in the upper part of figure 7.10, above the corresponding surface of section for the actual driven pendulum. The perturbative solution captures many features seen on the actual section. The shapes of the resonance regions are distorted by the transformations that eliminate the nearby resonances, so the resulting pieces fit together consistently. The predicted width of each resonance region agrees with the actual width: it is not substantially changed by the distortion of the region introduced by the elimination of the other resonance terms. But not all the features of the actual section are reproduced in this composite of first-order approximations. The first-order perturbative solution does not capture the resonant islands between the two primary resonances or the secondary island chains contained within a primary resonance region. Also, the first-order perturbative solution does not show the chaotic zone near the separatrix apparent in the surface of section for the actual driven pendulum.

For larger drives, the approximations derived by first-order perturbations are worse. In the lower part of figure 7.11, with drive larger by a factor of five, we lose the invariant curves that separate the resonance regions. The main resonance islands persist, but the chaotic zones near the separatrices have merged into one large chaotic sea.

The composite first-order perturbative solution for the more strongly driven pendulum in the upper part of figure 7.11 still approximates the centers of the main resonance islands reasonably well, but it fails as we move out and encounter the secondary islands that are visible in the resonance region for ωr(p) = ω. Here the approximations for the two regions do not fit together so well. The chaotic sea is found in the region where the perturbative solutions do not match.

7.4.2 Reading the Hamiltonian

The locations and widths of the primary resonance islands can often be read straight off the Hamiltonian when expressed as a Poisson series. For each term in the series for the perturbation there is a corresponding resonance island. The width of the island can often be simply computed from the coefficients in the Hamiltonian. So just by looking at the Hamiltonian we can get a good idea of what sort of behavior we will see on the surface of section. For instance, in the driven pendulum, the Hamiltonian (7.54) has three terms. We could anticipate, just from looking at the Hamiltonian, that three main resonance islands are to be found on the surface of section. We know that these islands will be located where the resonant combination of angles is slow. So for the periodically driven pendulum the resonances occur near ωr(p) = ω, ωr(p) = 0, and ωr(p) = −ω. The approximate widths of the resonance islands can be computed with a simple calculation.

7.4.3 Resonance-Overlap Criterion

As the size of the drive increases, the chaotic zones near the separatrices get larger and then merge into a large chaotic sea. The resonance-overlap criterion gives an analytic estimate of when this occurs. The basic idea is to compare the sum of the widths of neighboring resonances with their separation. If the sum of the half-widths is greater than the separation, then the resonance-overlap criterion predicts there will be large-scale chaotic behavior near the overlapping resonances. In the case of the periodically driven pendulum, the half-width of the ωr(p) = 0 resonance is

The amplitude of the drive enters through γ. Solving, we find the value of γ above which resonance overlap occurs. For the parameters α = β = 1, ω = 5 used in figures 7.9–7.11, the resonance overlap value of γ is 9/4. We see that, in fact, the chaotic zones have already merged for γ = 5/4. So in this case the resonance-overlap criterion overestimates the strength of the resonances required to get large-scale chaotic behavior. This is typical of the resonance-overlap criterion.

A way of thinking about why the resonance-overlap criterion usually overestimates the strength required to get large-scale chaos is that other effects must be taken into account. For instance, as the drive is increased second-order resonances appear between the primary resonances; these resonances take up space and so resonance overlap occurs for smaller drive than would be expected by considering the primary resonances alone. Also, the chaotic zones at each separatrix have area that must be accounted for.

7.4.4 Higher-Order Perturbation Theory

As the drive is increased, a variety of new islands emerge, which are not evident in the original Hamiltonian. To find approximations for motion in these regions we can use higher-order perturbation theory. The basic plan is the same as before. At any stage the Hamiltonian (which is perhaps a result of earlier stages of perturbation theory) is expressed as a Poisson series (a multiple-angle Fourier series). The terms that are not resonant in a region of interest are eliminated by a Lie transformation. The remaining resonance terms involve only a single combination of angle and are thus solvable by making a canonical transformation to resonance coordinates. We complete the solution and transform back to the original coordinates.

Let’s find a perturbative approximation for the second-order islands visible in figure 7.10 between the ωr(p) = 0 resonance and the ωr(p) = −ω resonance. The details are messy, so we will just give a few intermediate results.

This resonance is not near the three primary resonances, so we can use the full generator (7.56) to eliminate those three primary resonance terms from the Hamiltonian. After this perturbation step the Hamiltonian is too hairy to look at.

We expand the transformed Hamiltonian in Poisson form and divide the terms into those that are resonant and those that are not. The terms that are not resonant can be eliminated by a Lie transform. This Lie transform leaves the resonant terms in the Hamiltonian and introduces an additional distortion to the curves on the surface of section. In this case this additional distortion is small, but very messy to compute, so we will just not include this effect. The resonance Hamiltonian is then (after considerable algebra)

This is solvable because there is only a single combination of coordinates.

We can get an analytic solution by making the pendulum approximation. The Hamiltonian is already quadratic in the momentum p, so all we need to do is evaluate the coefficient of the potential terms at the resonance center p2:1 = αω/2. The resonance Hamiltonian, in the pendulum approximation, is

Carrying out the transformation to the resonance variable σ = 2θ − ωt reduces this to a pendulum Hamiltonian with a single degree of freedom. Combining the analytic solution of this pendulum Hamiltonian with the transformations generated by the full W, we get an approximate perturbative solution

A surface of section in the appropriate resonance region using this solution is shown in figure 7.13. Comparing this to the actual surface of section (figure 7.10), we see that the approximate solution provides a good representation of this resonance motion.

7.4.5 Stability of the Inverted Vertical Equilibrium

As a second application, we use second-order perturbation theory to investigate the inverted vertical equilibrium of the periodically driven pendulum.

Here, the procedure parallels the one just followed, but we focus on a different set of resonance terms. The terms that are slowly varying for the vertical equilibrium are those that involve θ but do not involve t, such as cos(θ) and cos(2θ). So we want to use the generator W+ + W− that eliminates the nonresonant terms involving combinations of θ and ωt, while leaving the central resonance. After the Lie transform of the Hamiltonian with this generator, we write the transformed Hamiltonian as a Poisson series and collect the resonant terms. The transformed resonance Hamiltonian is

Figure 7.14 shows contours of this resonance Hamiltonian

We can get an analytic estimate for the stability of the inverted vertical equilibrium by carrying out a linear stability analysis of the fixed point θ = π, p = 0 of the resonance Hamiltonian. The algebra is somewhat simpler if we first make the pendulum approximation about the resonance center. The resonance Hamiltonian is then approximately

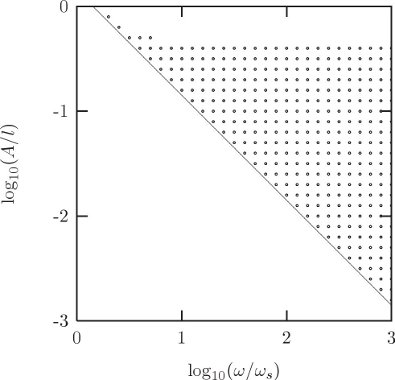

Linear stability analysis of the inverted vertical equilibrium indicates stability for

In terms of the original physical parameters, the vertical equilibrium is linearly stable if

where

This analytic estimate is compared with the behavior of the driven pendulum in figure 7.15. For any given assignment of the parameters, the driven pendulum can be tested for the linear stability of the inverted vertical equilibrium by the methods of chapter 4; this involves determining the roots of the characteristic polynomial for a reference orbit at the resonance center. In the figure the stability of the inverted vertical equilibrium was assessed at each point of a grid of assignments of the parameters. A dot is shown for combinations of parameters that are linearly stable. The diagonal line is the analytic boundary of the region of stability of the inverted equilibrium:

7.5 Summary

The goal of perturbation theory is to relate aspects of the motions of a given system to those of a nearby solvable system. Perturbation theory can be used to predict features such as the size and location of the resonance islands and chaotic zones.

With perturbation analysis we obtain an approximation to the evolution of a system by relating the evolution of the system to that of a different system that, when approximated, can be exactly solved. We can carry this exact solution of the approximate problem back to the original system to obtain an approximate solution of our original problem. The strategy of canonical perturbation theory is to make canonical transformations that eliminate terms in the Hamiltonian that impede solution. Formulation of perturbation theory in terms of Lie series is especially convenient.

We can use first-order perturbation theory to analyze the motion of the undriven pendulum as a free rotor to which gravity is added. In this analysis we find that a small denominator in the series limits the range of applicability of the perturbative solution to regions that are away from the resonant oscillation region.

In higher-order perturbation theory for the pendulum we discover the problem of secular terms, terms that produce error that grow with time. The appearance of secular terms can be avoided by keeping track of how the frequencies change as perturbations are included. In canonical perturbation theory secular terms can be avoided by associating the average part of the perturbation with the solvable part of the Hamiltonian.

In carrying out canonical perturbation theory in higher dimensions we find that the problem of small denominators is more serious. Small denominators arise near every commensurability, and commensurabilities are common. Small denominators can be locally avoided near particular commensurabilities by incorporating the offending terms into the solvable part of the Hamiltonian. If the resonances are isolated, the resulting resonance Hamiltonian is still solvable. In many cases the resonance Hamiltonian is well approximated by a pendulum-like Hamiltonian. A global picture can be constructed by stitching together the solutions for each resonance region constructed separately.

If two resonance regions overlap—that is, if the sum of the half-widths of the resonance regions exceeds their separation—then large-scale chaos ensues. The chaotic regions associated with the separatrices of the overlapping resonances become connected. When the resonances are well approximated by pendulum-like resonances a simple analytic criterion for the appearance of large-scale chaos can be developed.

Higher-order perturbative descriptions can be developed to describe islands that do not correspond to particular terms in the Hamiltonian, secondary resonances, bifurcations, and so on. The theory can be extended to describe as much detail as one wishes.

7.6 Projects

Exercise 7.4: Periodically driven pendulum

a. Work out the details of the perturbation theory for the primary driven pendulum resonances, as displayed in figure 7.10.

b. Work out the details of the perturbation theory for the stability of the inverted vertical equilibrium. Derive the resonance Hamiltonian and plot its contours. Compare these contours to surfaces of section for a variety of parameters.

c. Carry out the linear stability analysis leading to equation (7.88). What is happening in the upper part of figure 7.15? Why is the system unstable when criterion (7.88) predicts stability? Use surfaces of section to investigate this parameter regime.

Exercise 7.5: Spin-orbit coupling

A Hamiltonian for the spin-orbit problem described in section 2.11.2 is

where the ignored terms are higher order in eccentricity e. Note that here ϵ is the out-of-roundness parameter.

a. Find the widths and centers of the three primary resonances. Compare the predictions for the widths to the island widths seen on surfaces of section. Write the criterion for resonance overlap and compare to numerical experiments for the transition to large-scale chaos.

b. The fixed point of the synchronous island is offset from the average rate of rotation. This is indicative of a “forced” oscillation of the rotation of the Moon. Develop a perturbative theory for motion in the synchronous island by using a Lie transform to eliminate the two non-synchronous resonances. Predict the location of the fixed point at the center of the synchronous resonance on the surface of section, and thus predict the amplitude of the forced oscillation of the Moon.

1The “width” is measured as the range of momenta.

2In general, we need to include sine terms as well, but the cosine expansion is enough for this illustration.

3Any linearly independent combination will be acceptable here.

4For W+ see equations 7.74 and 7.75; for the general relationship between a term in the generator and the coordinate transformation generated see equations 7.48 and 7.49.